Welcome to Saxophonetics!

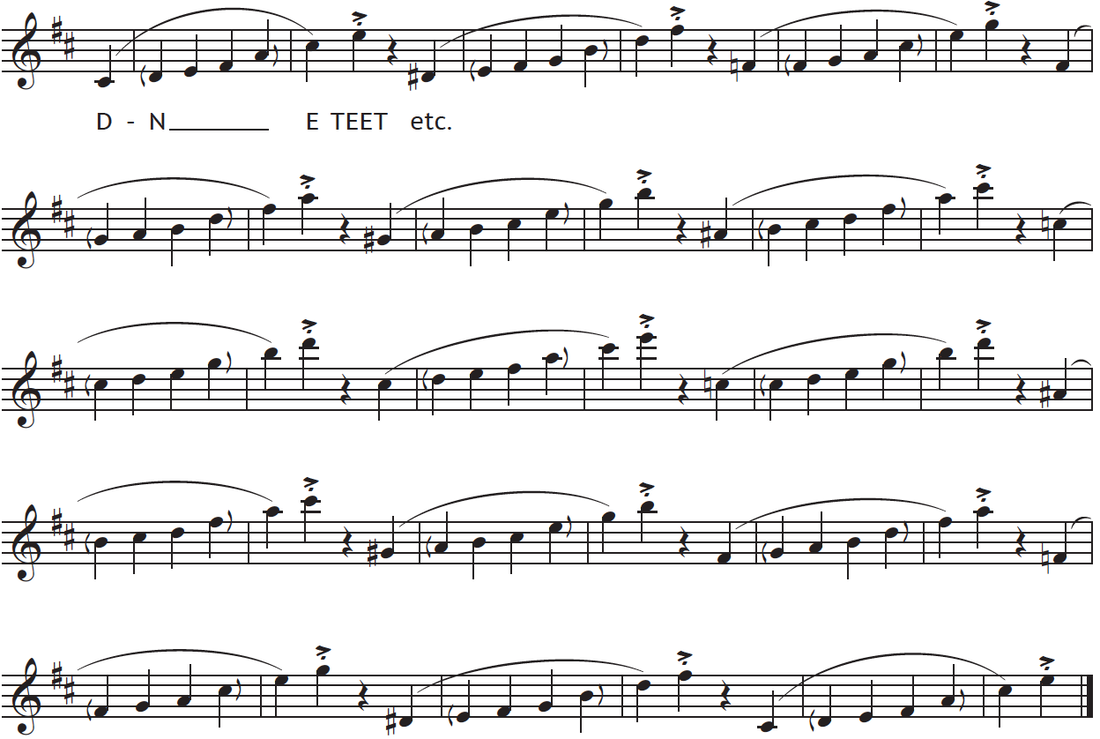

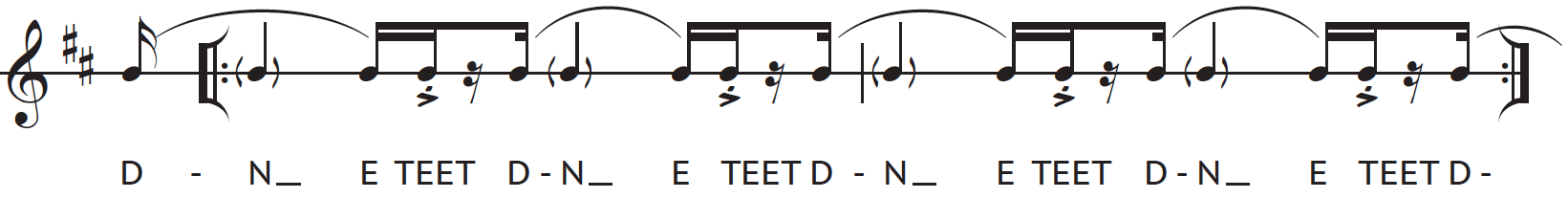

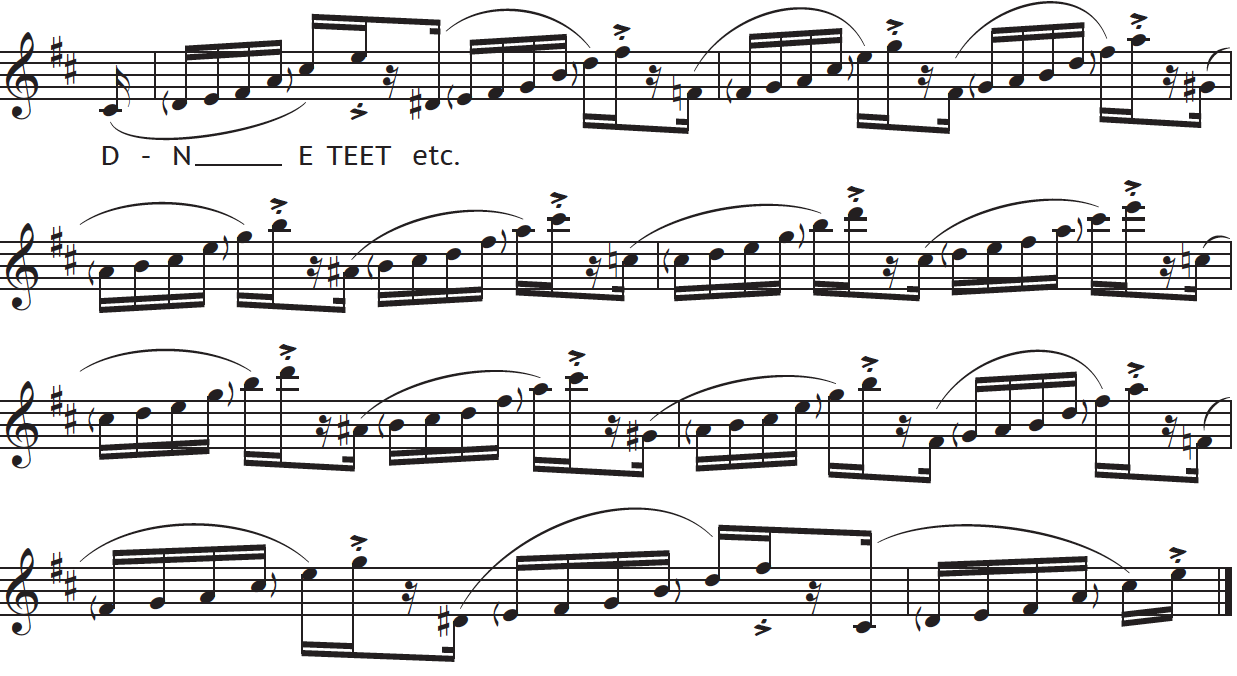

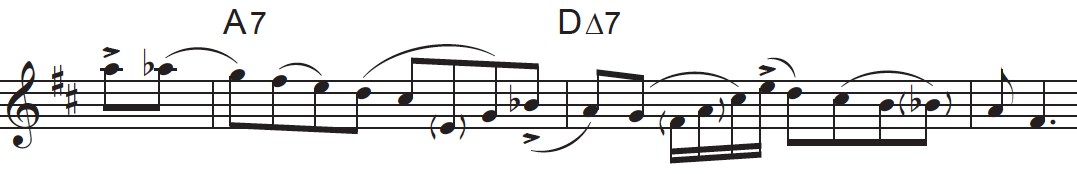

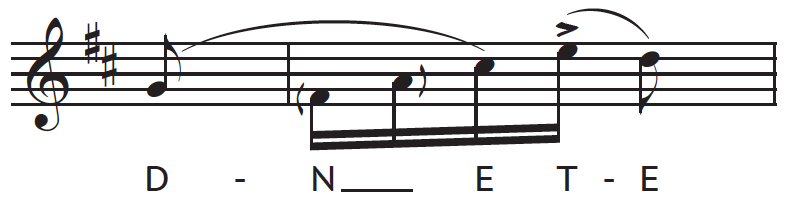

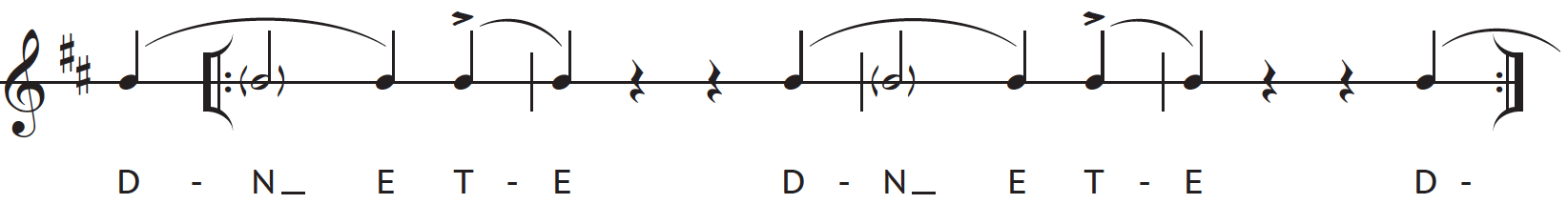

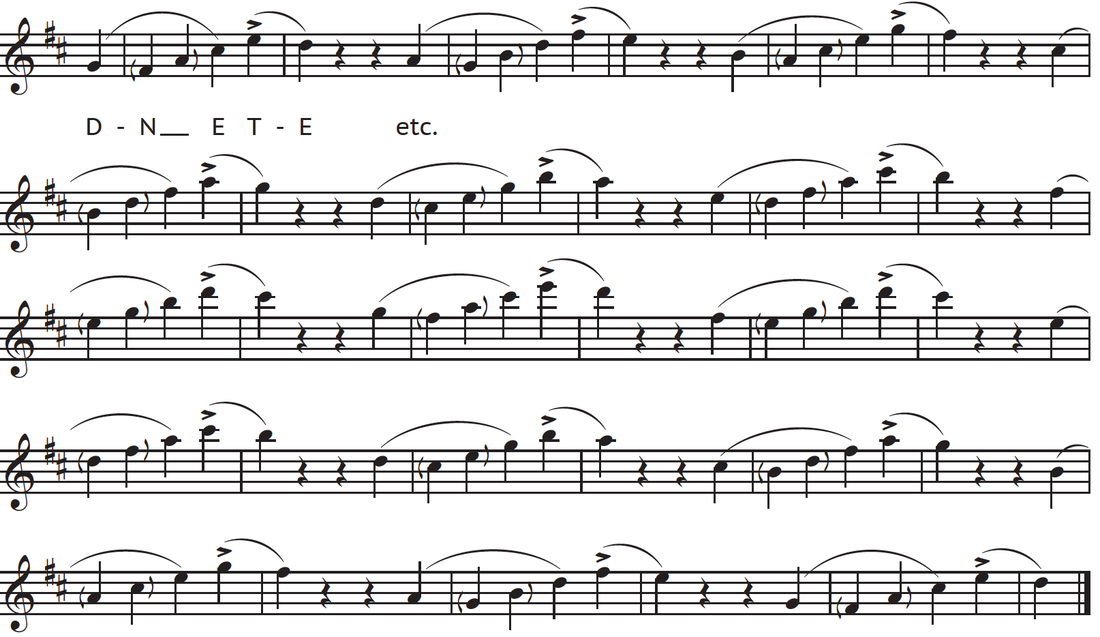

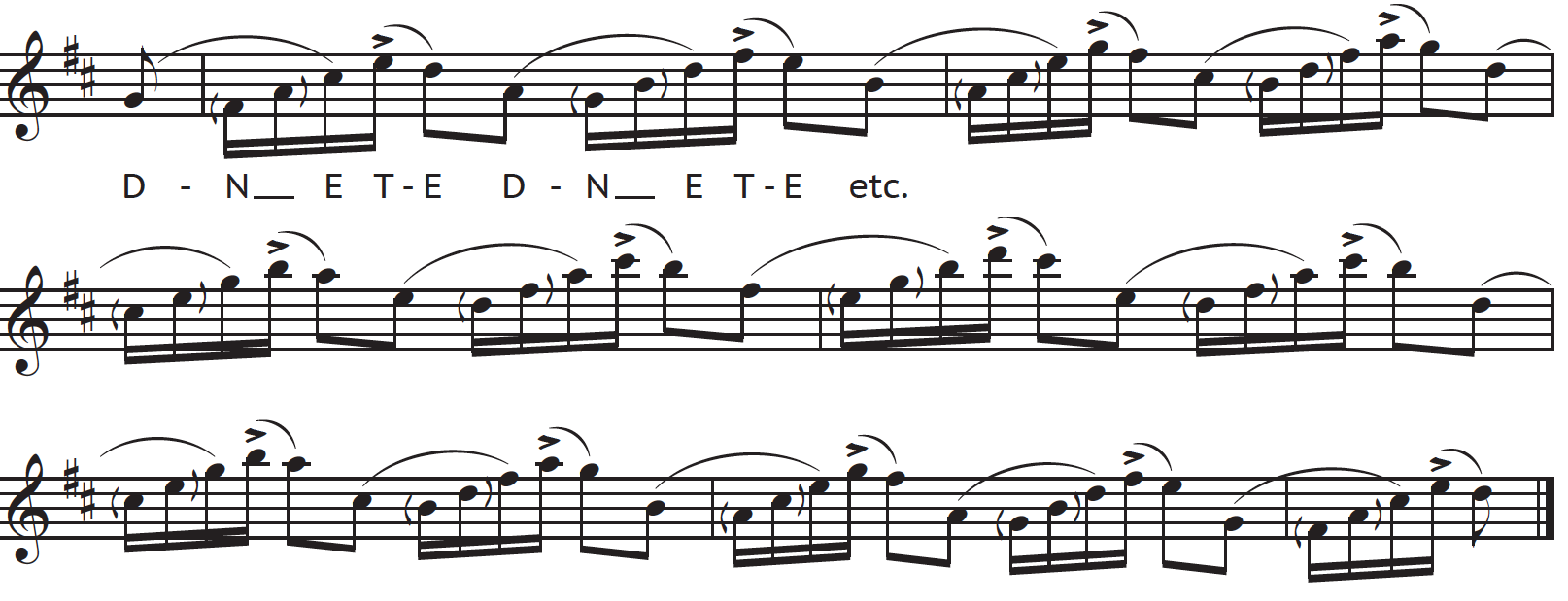

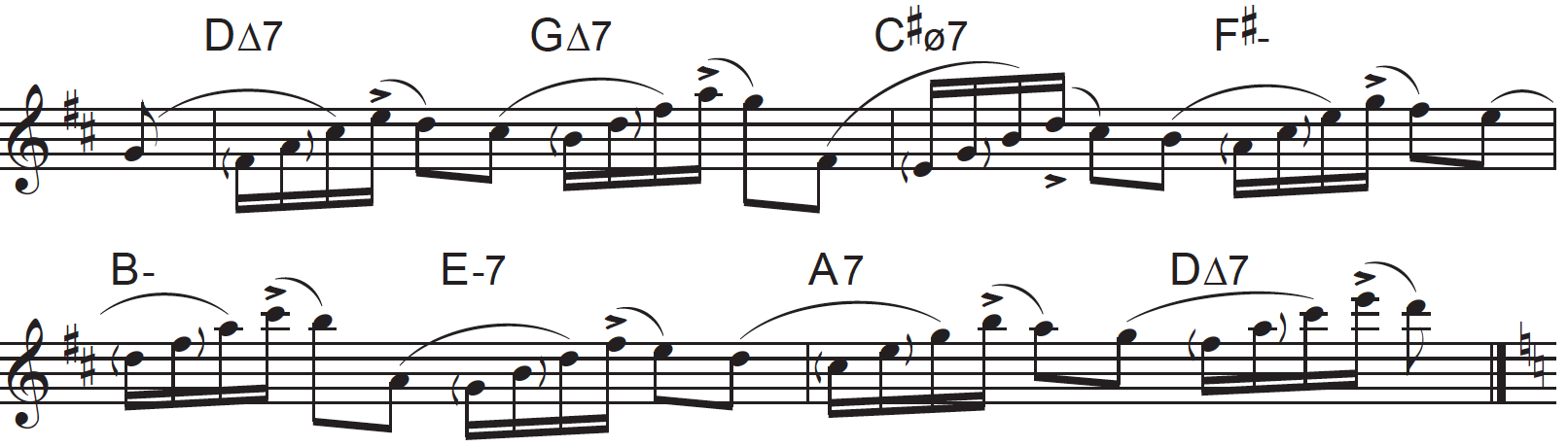

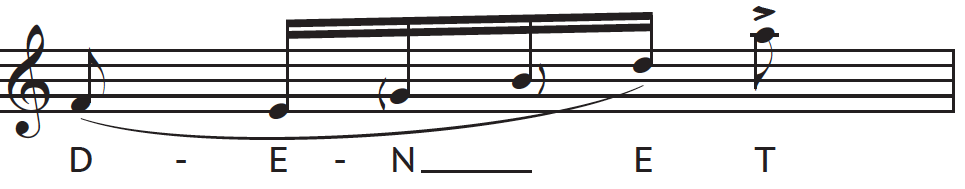

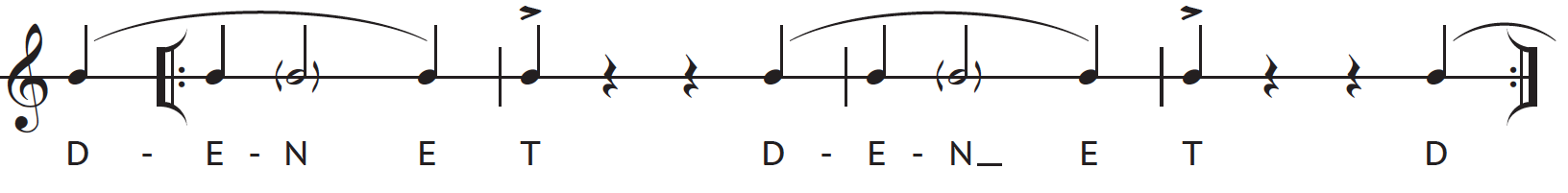

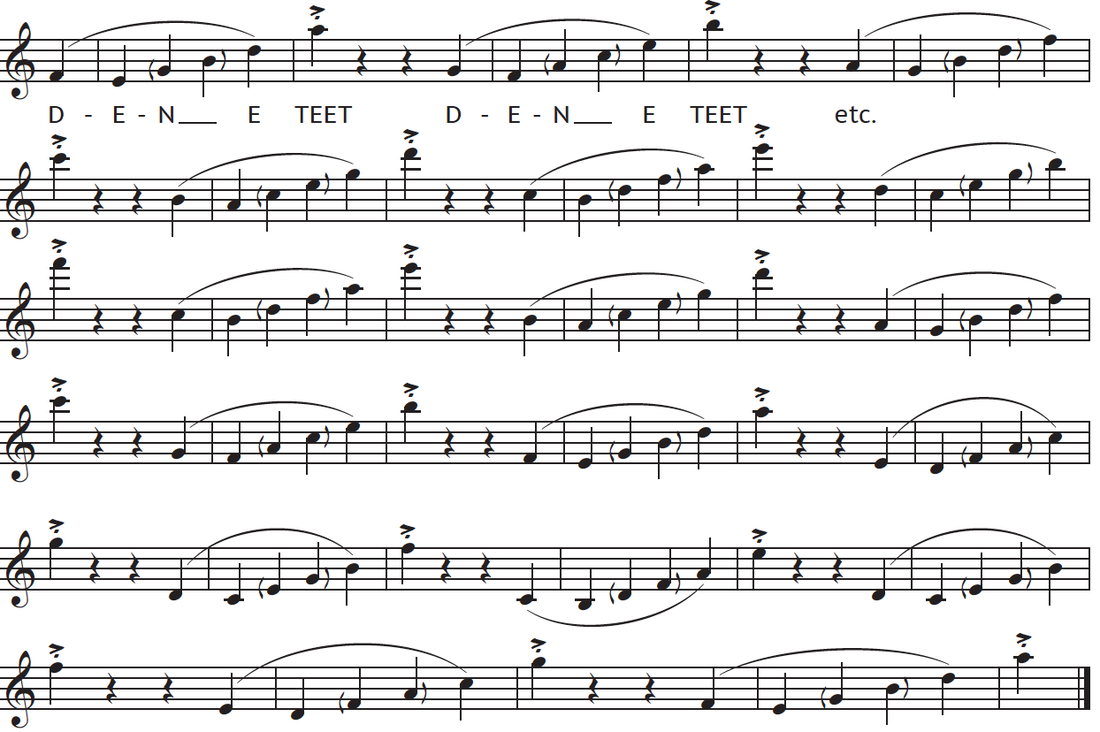

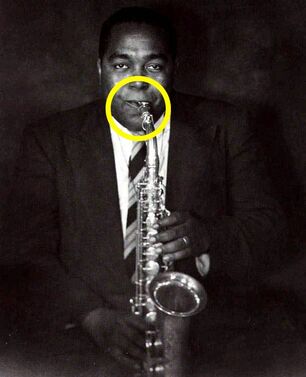

Developing an Authentic Jazz Saxophone Style

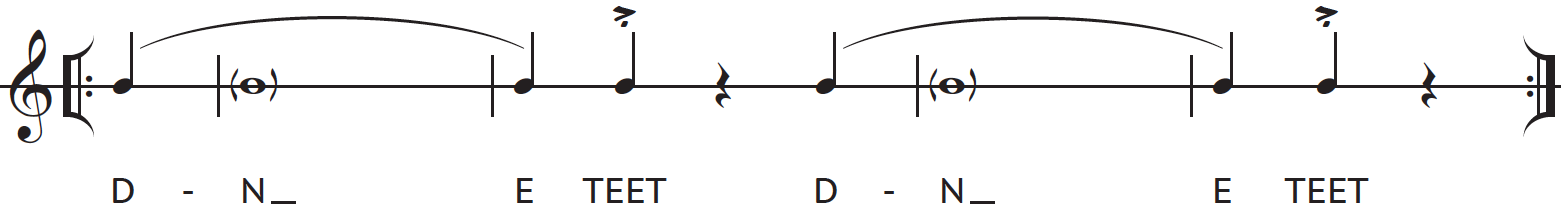

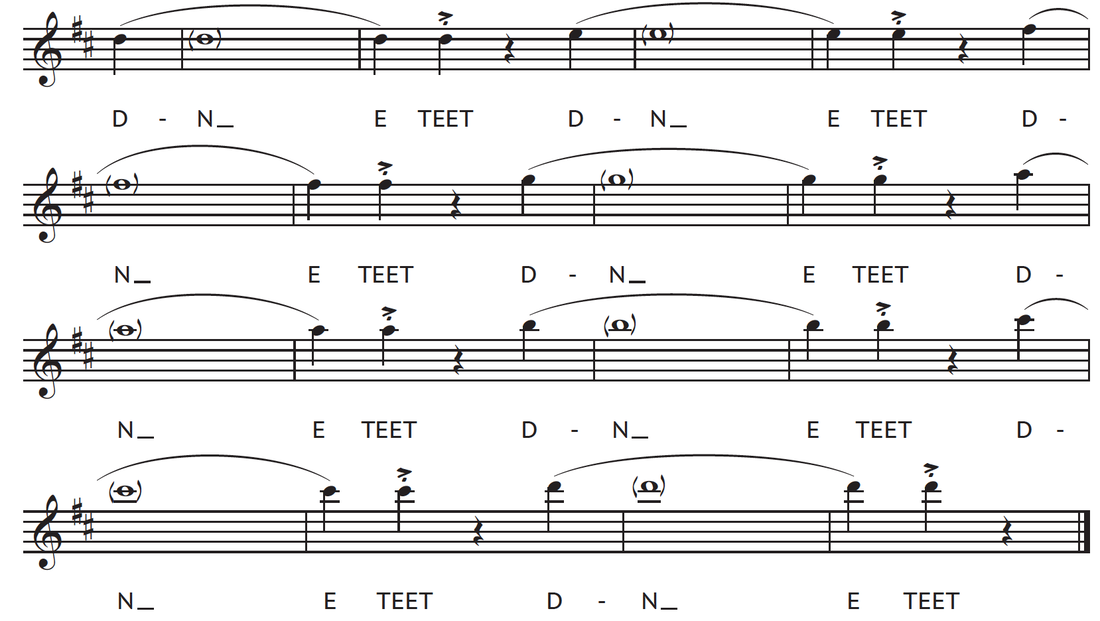

with a Focus On Articulation

with a Focus On Articulation

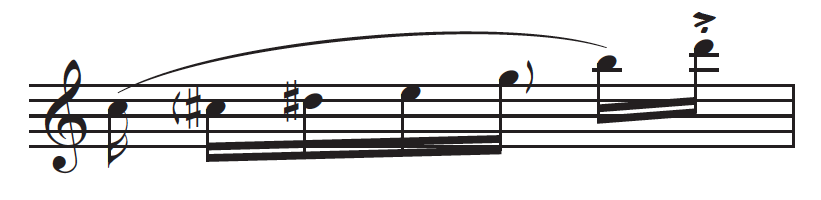

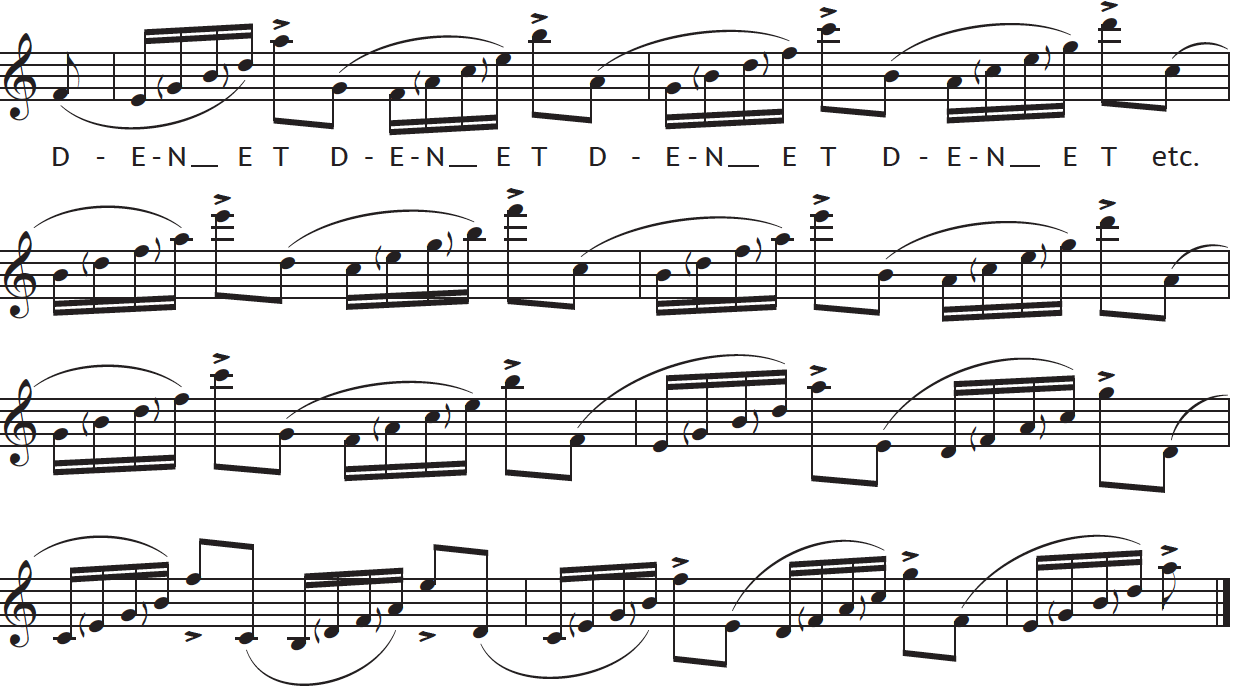

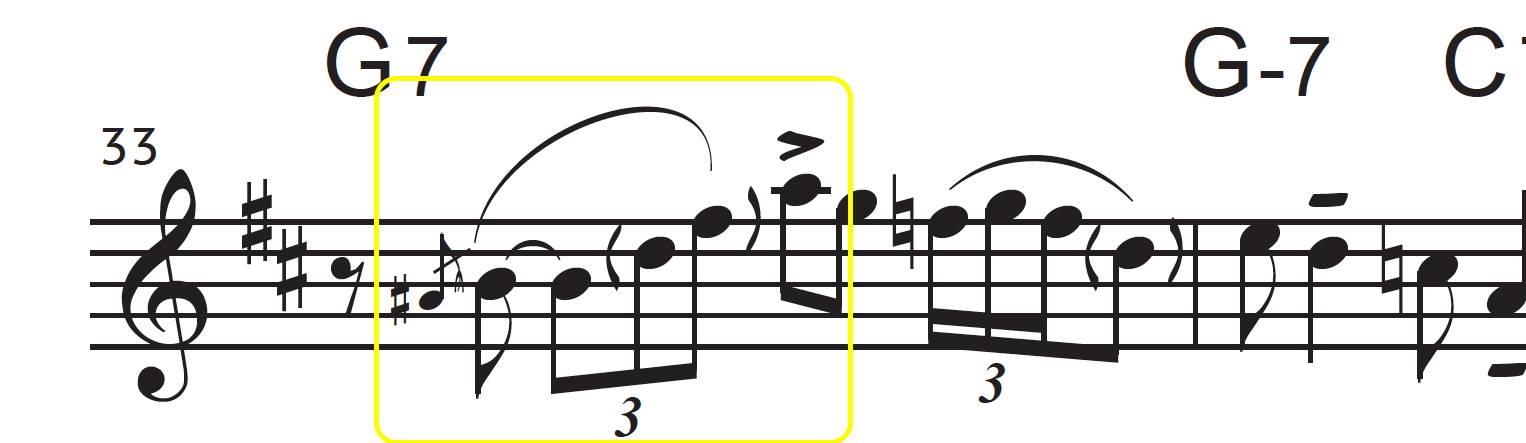

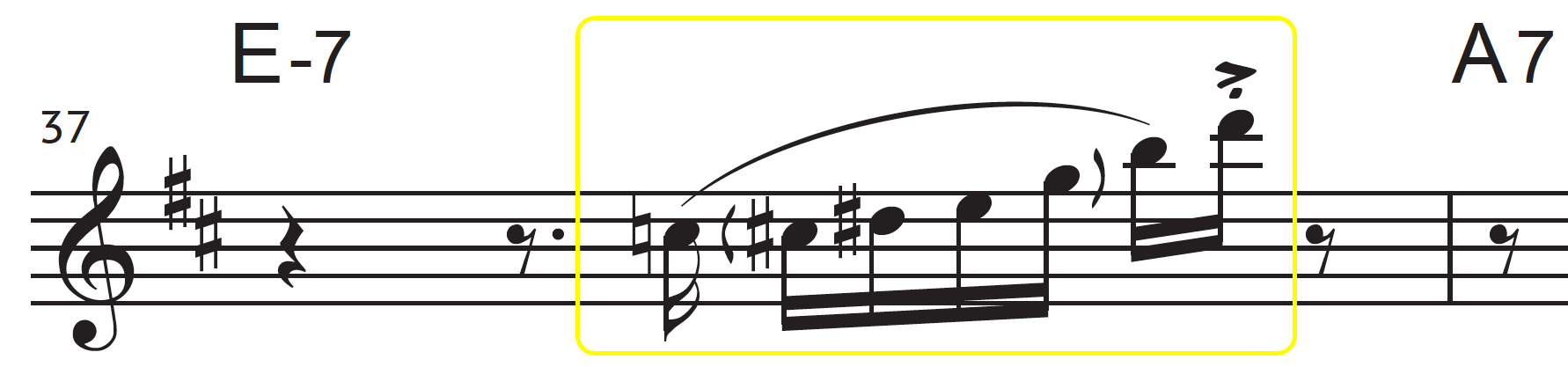

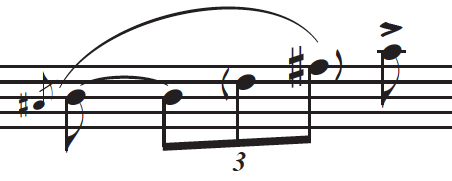

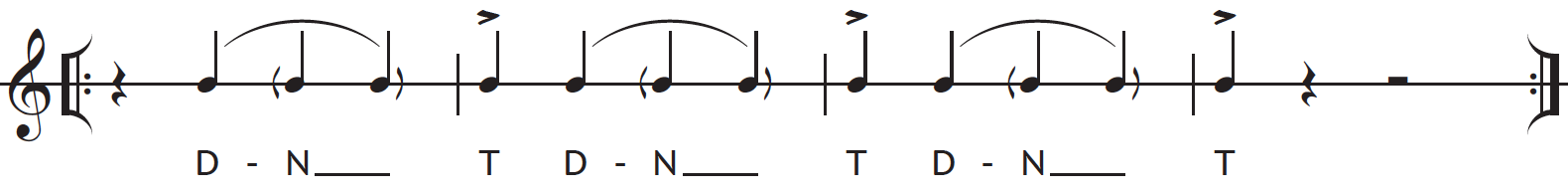

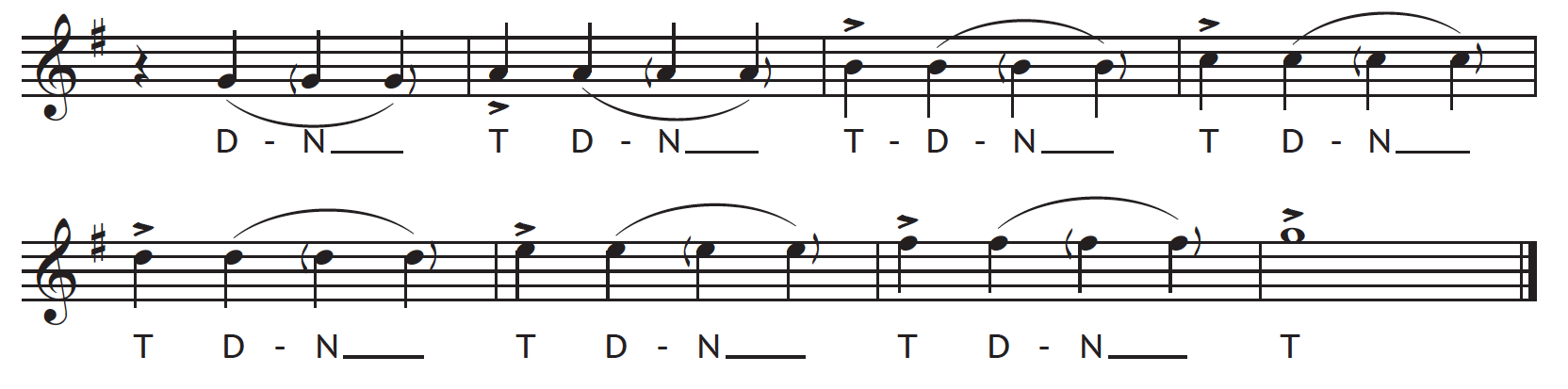

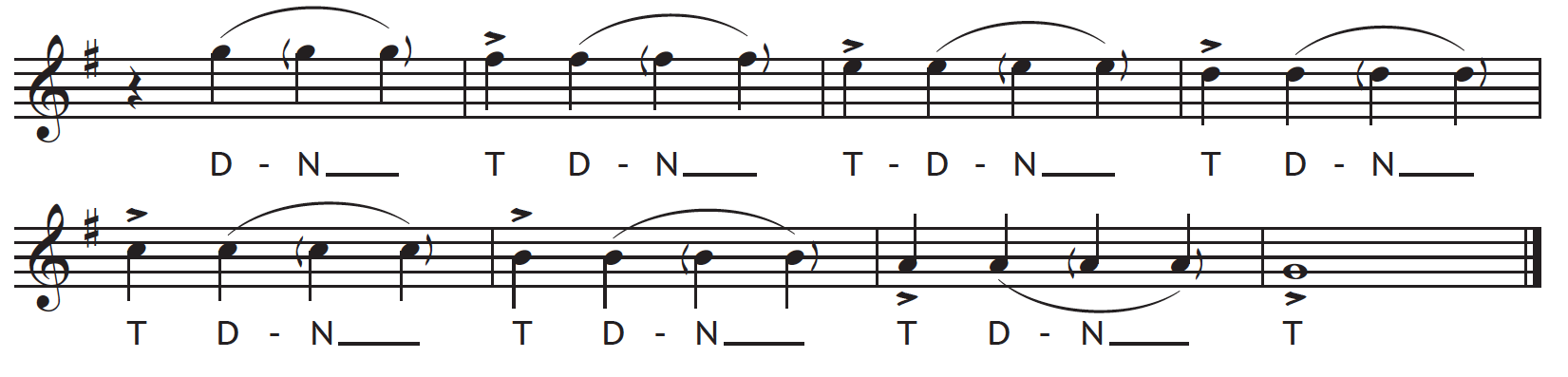

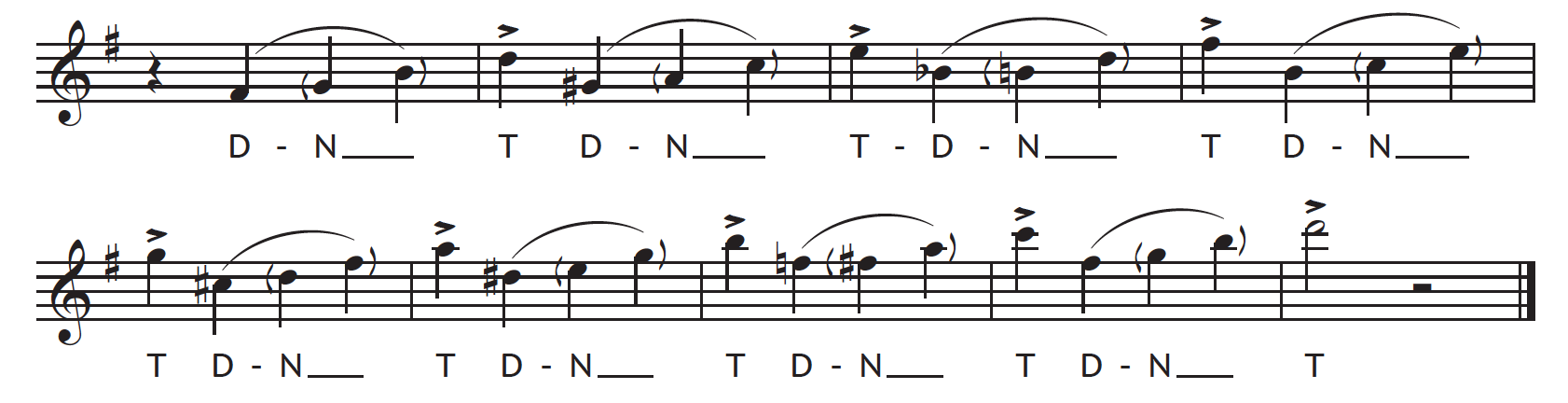

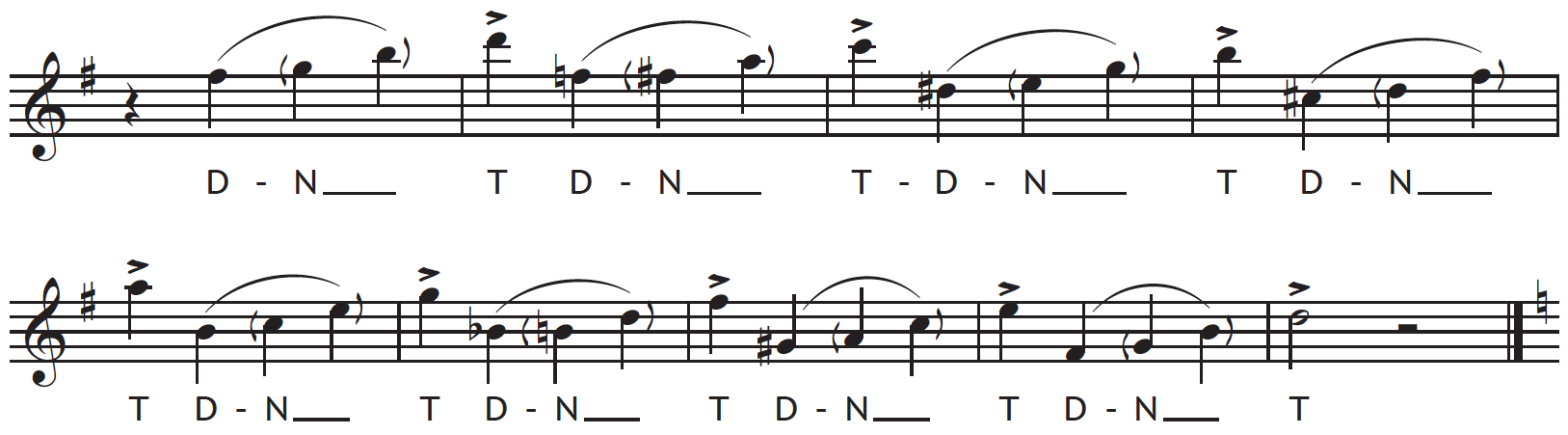

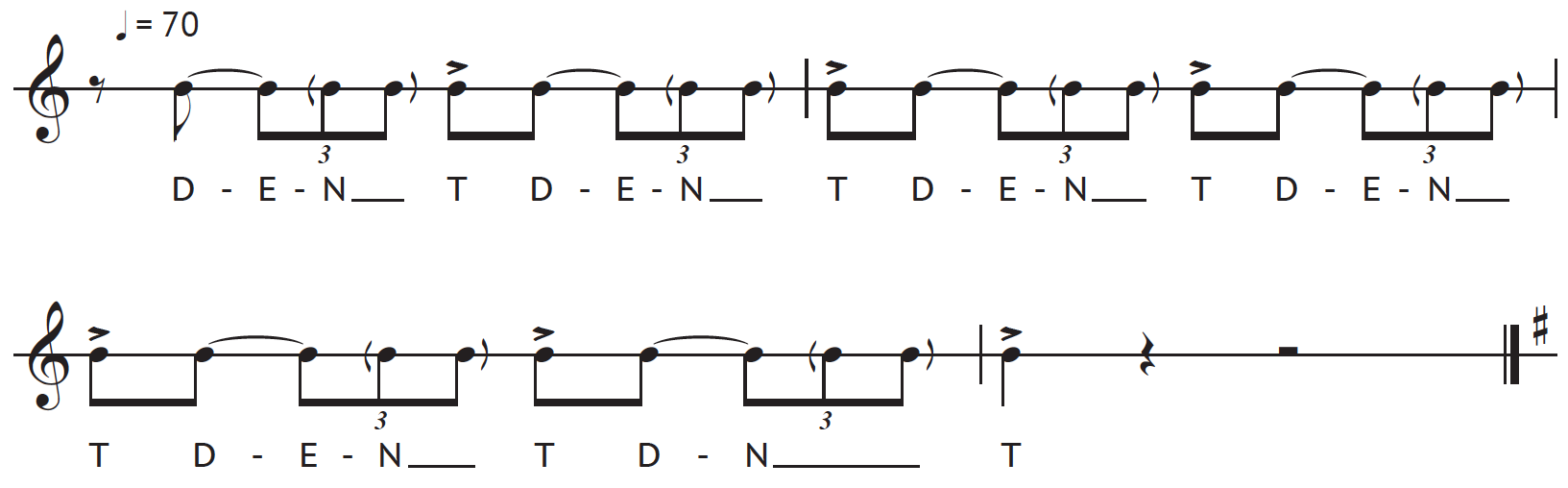

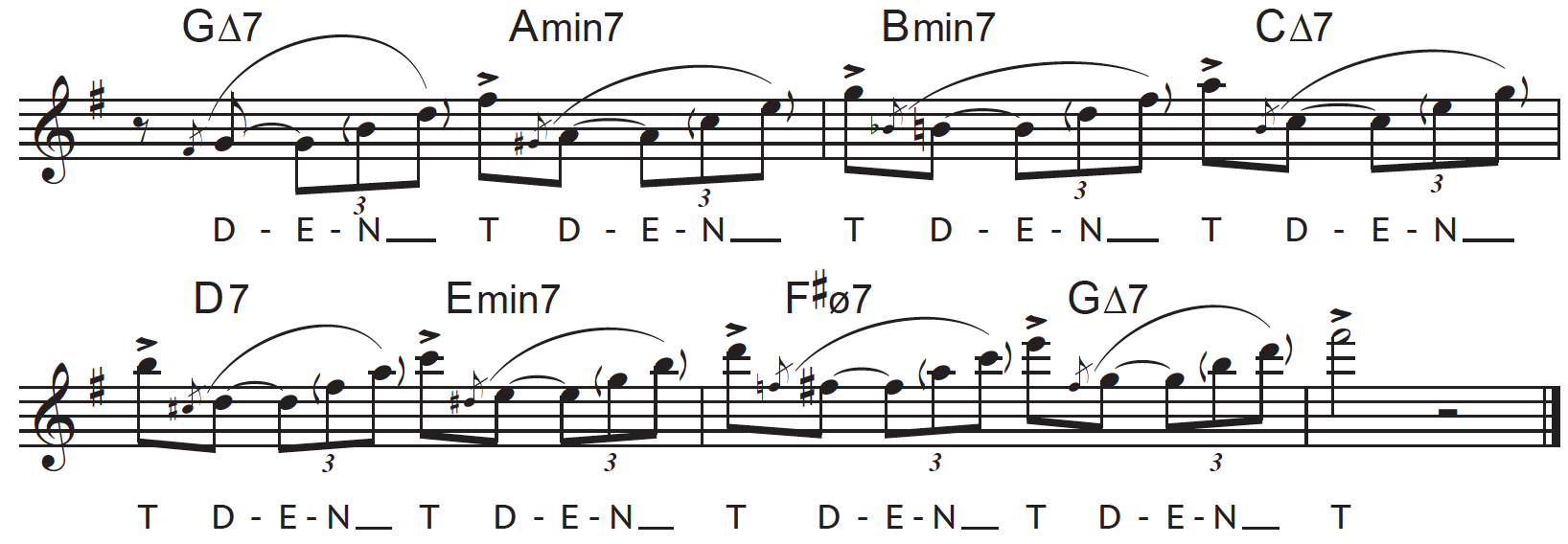

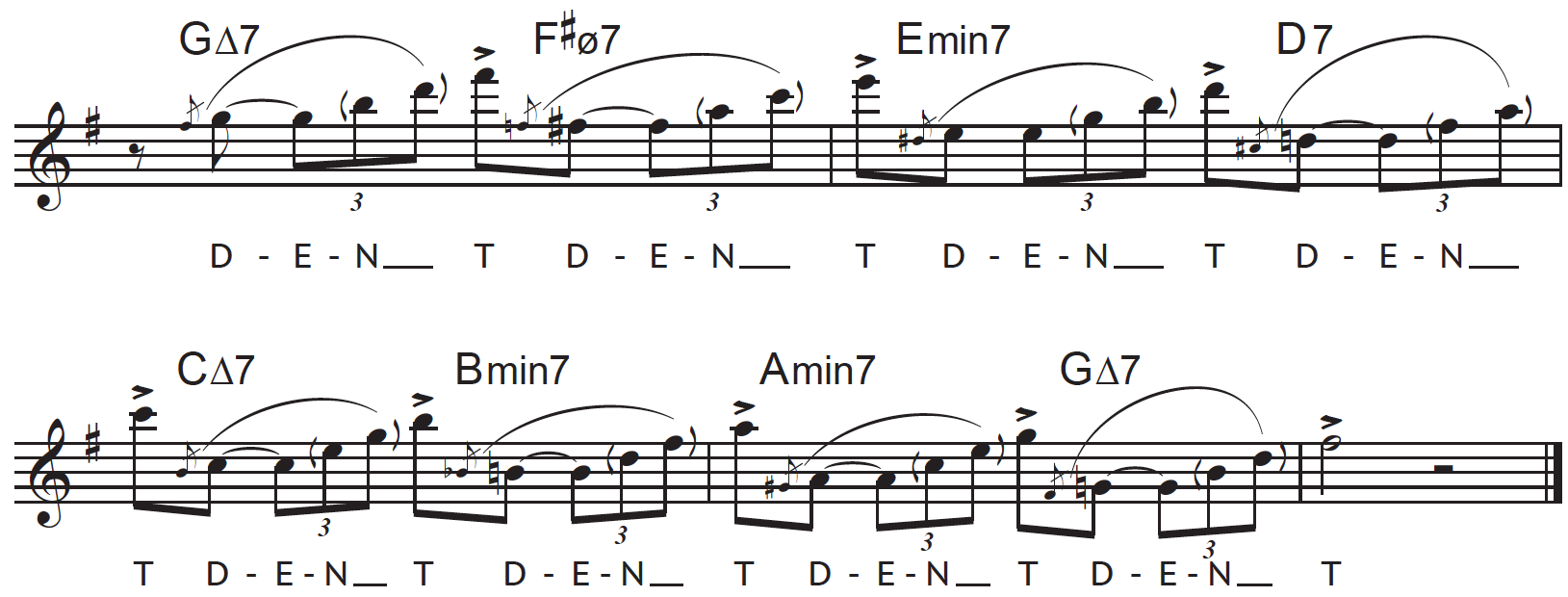

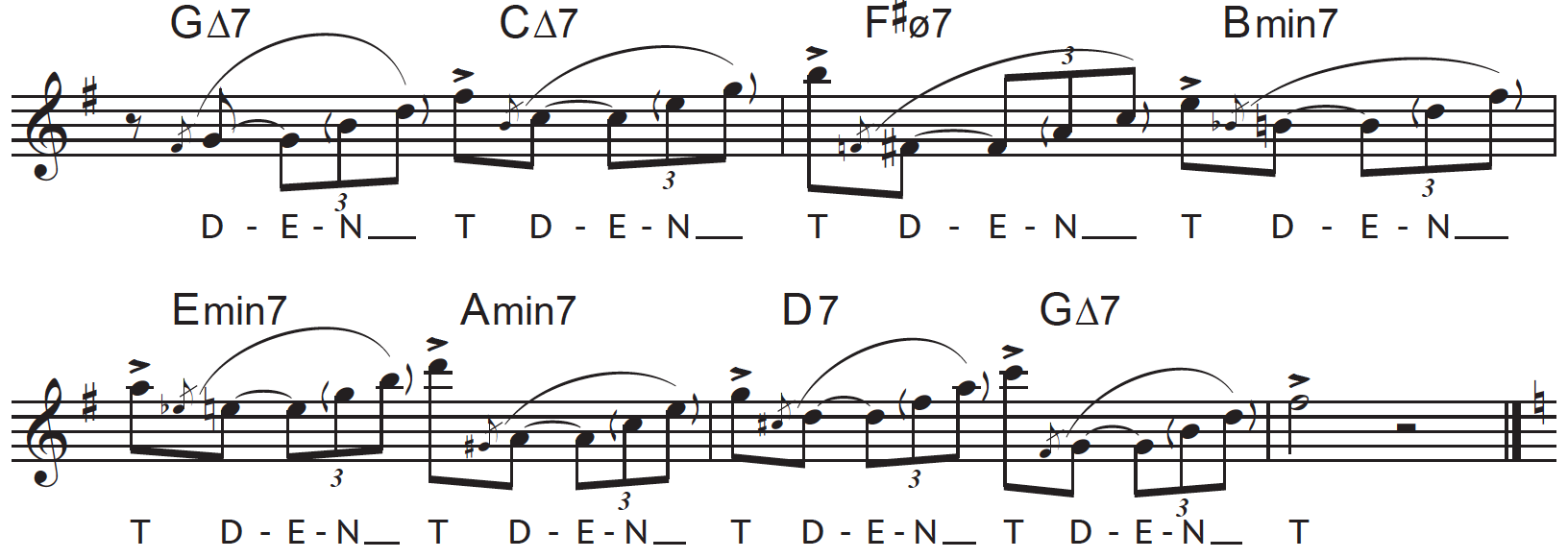

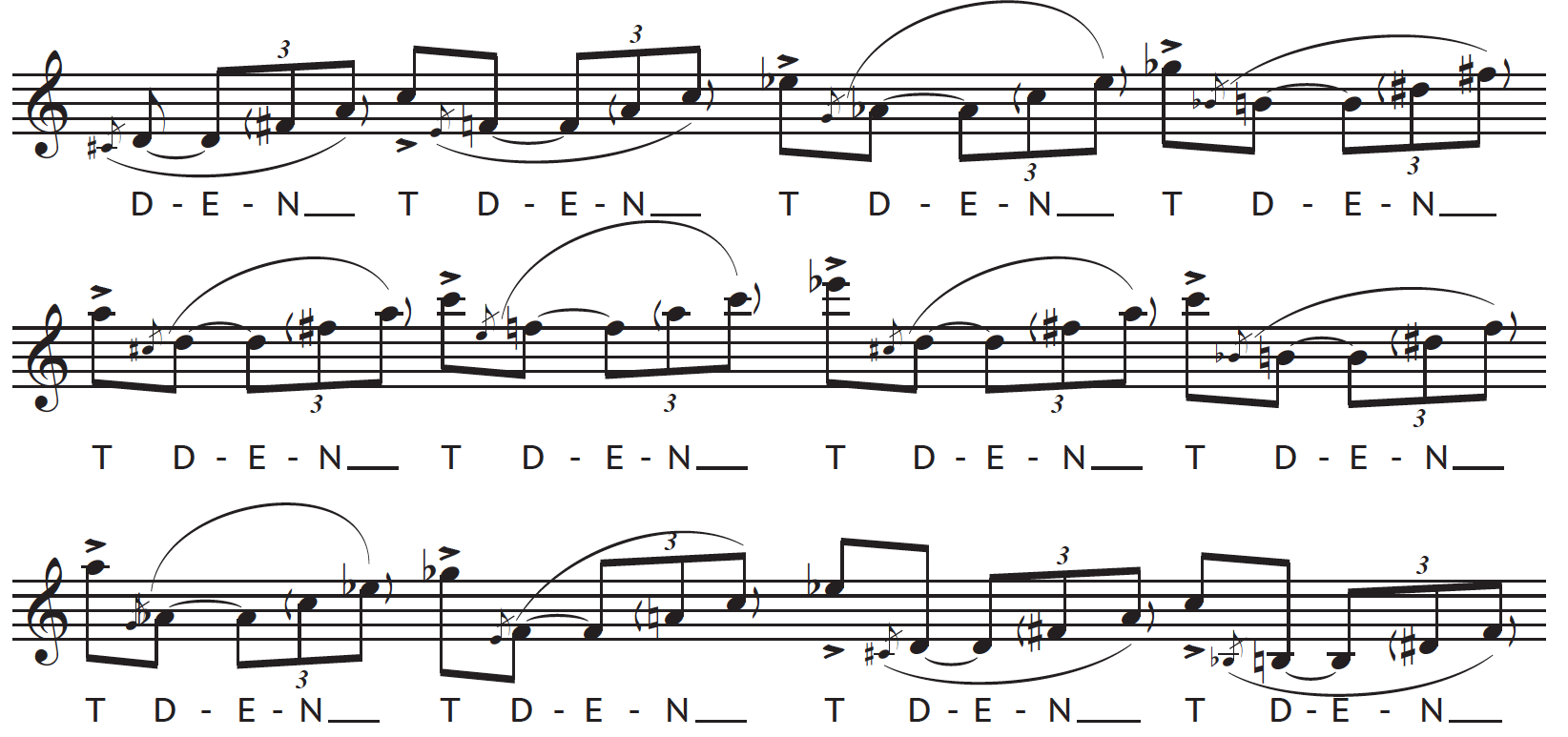

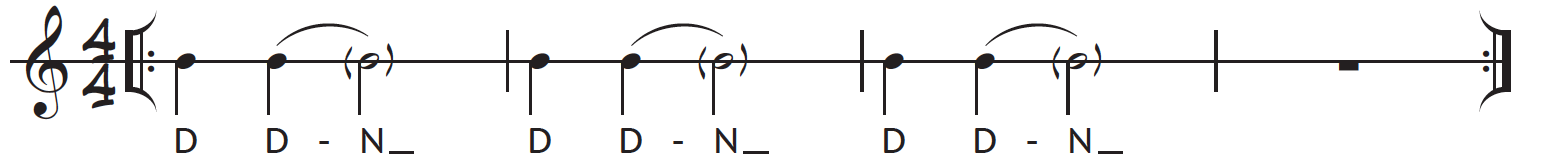

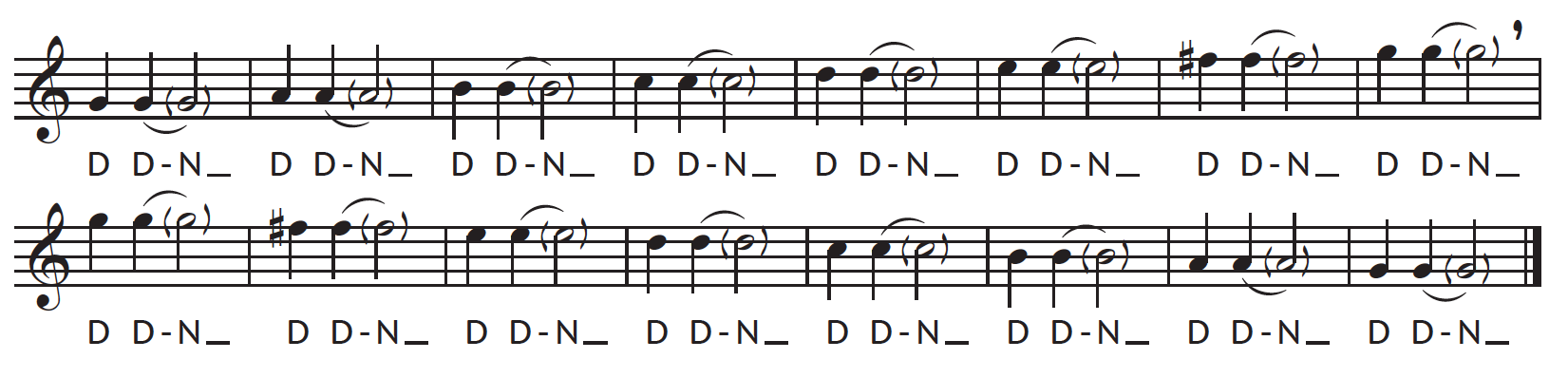

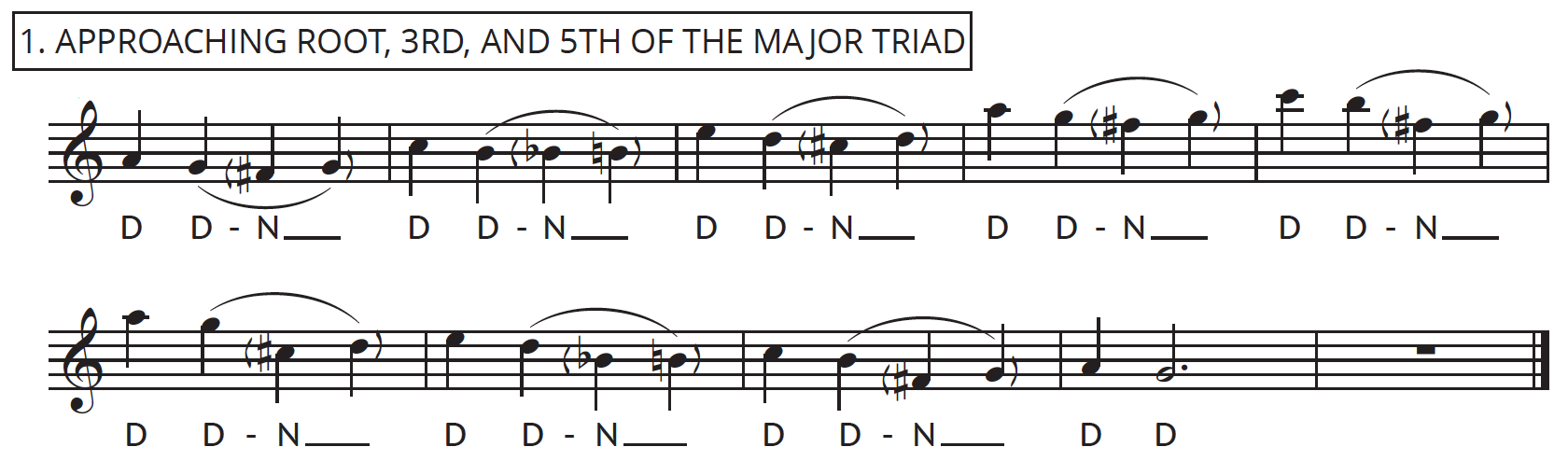

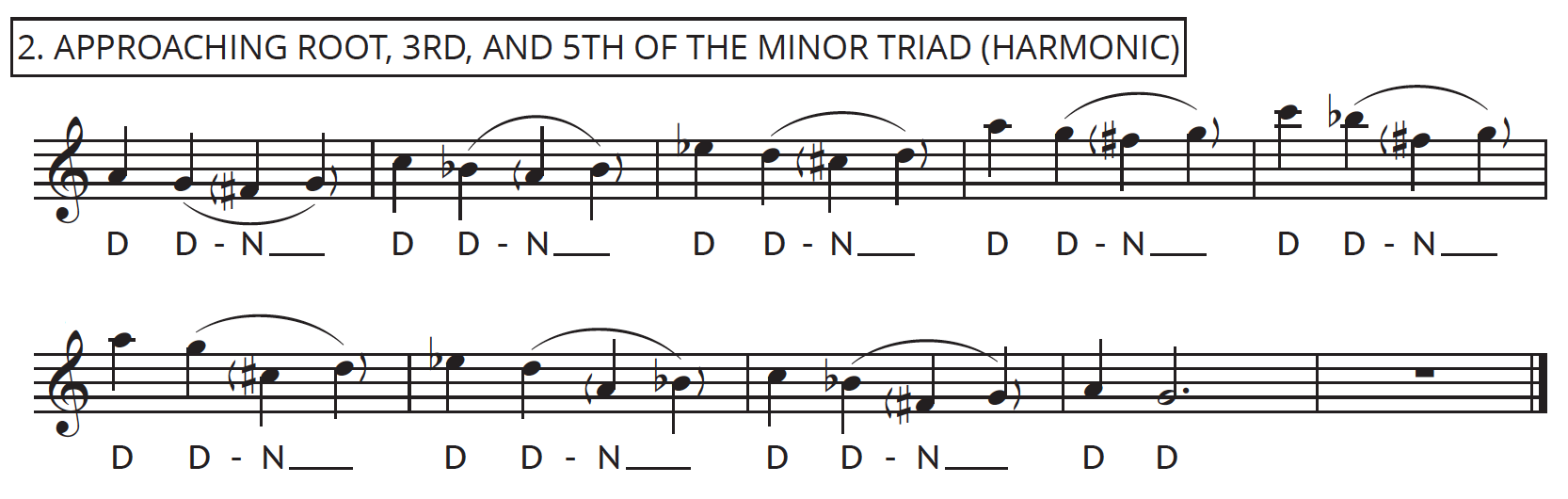

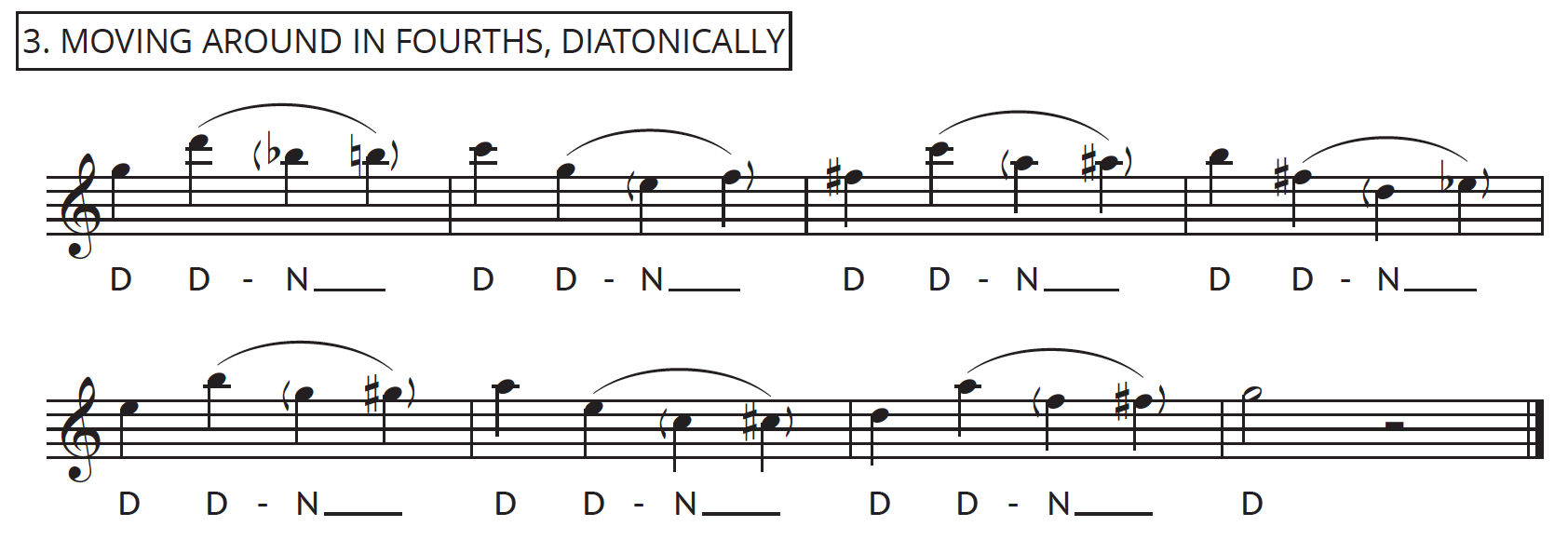

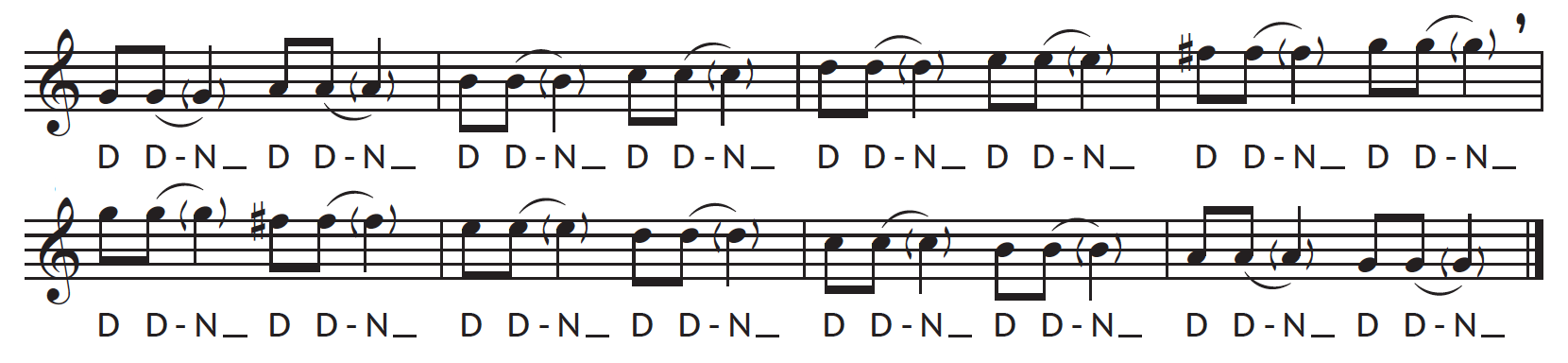

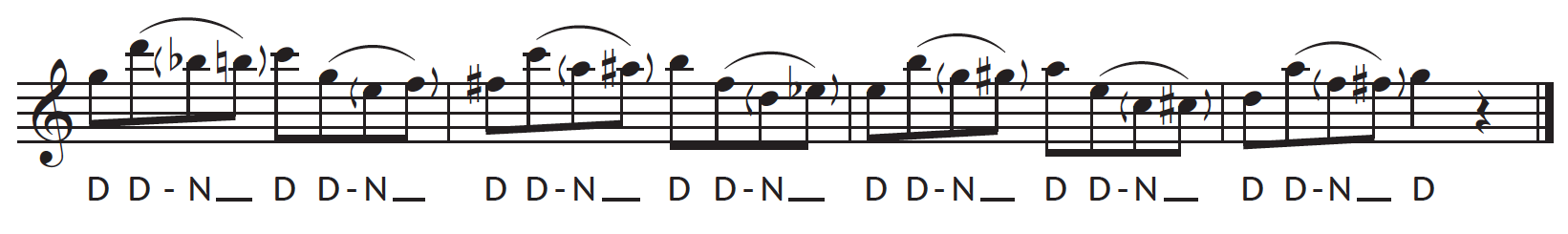

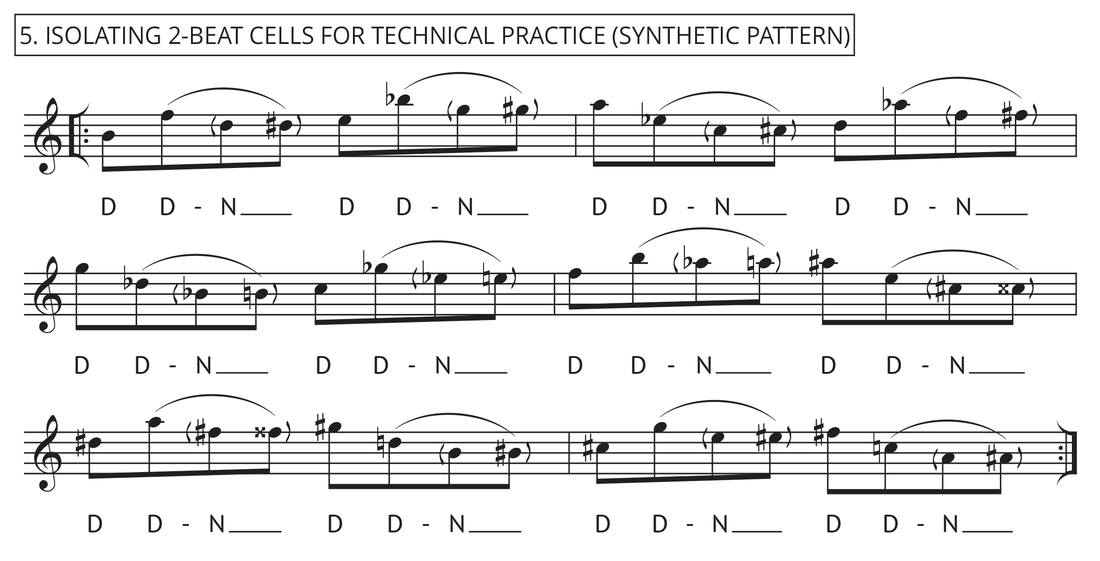

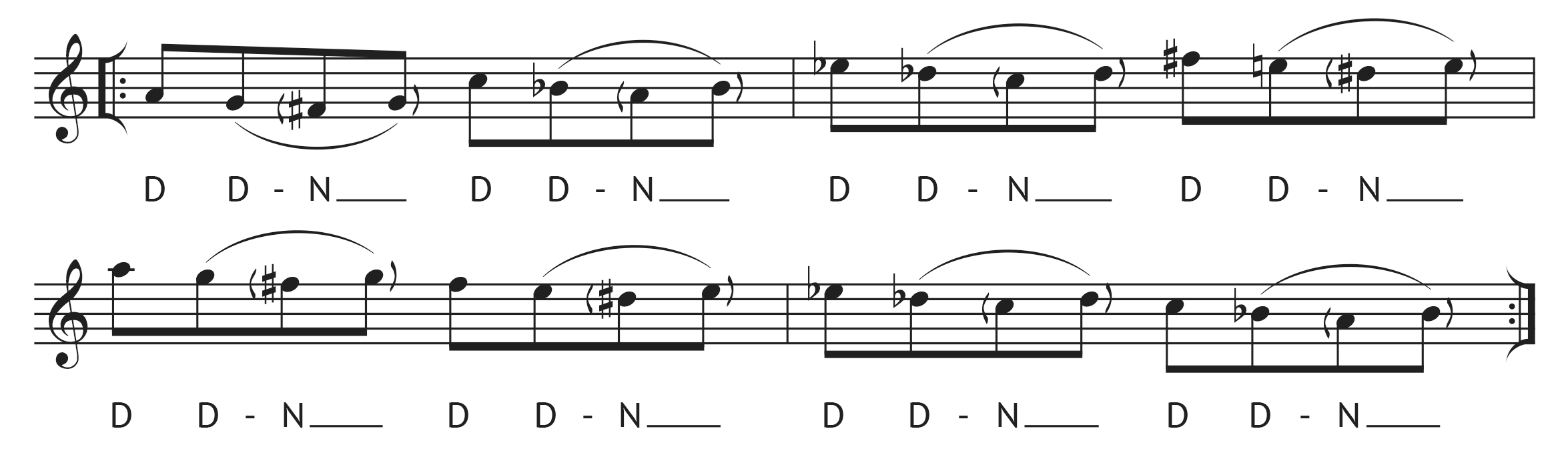

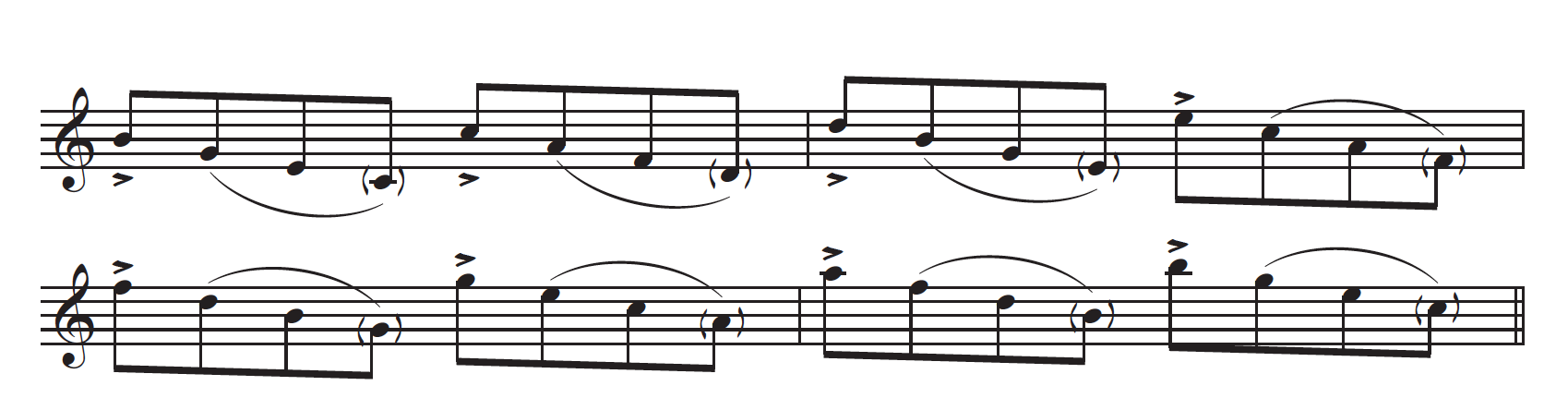

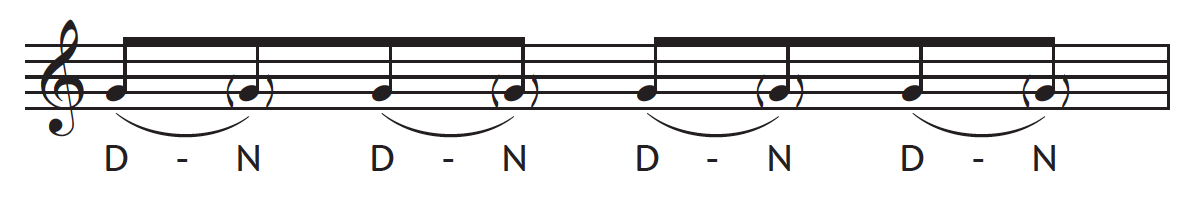

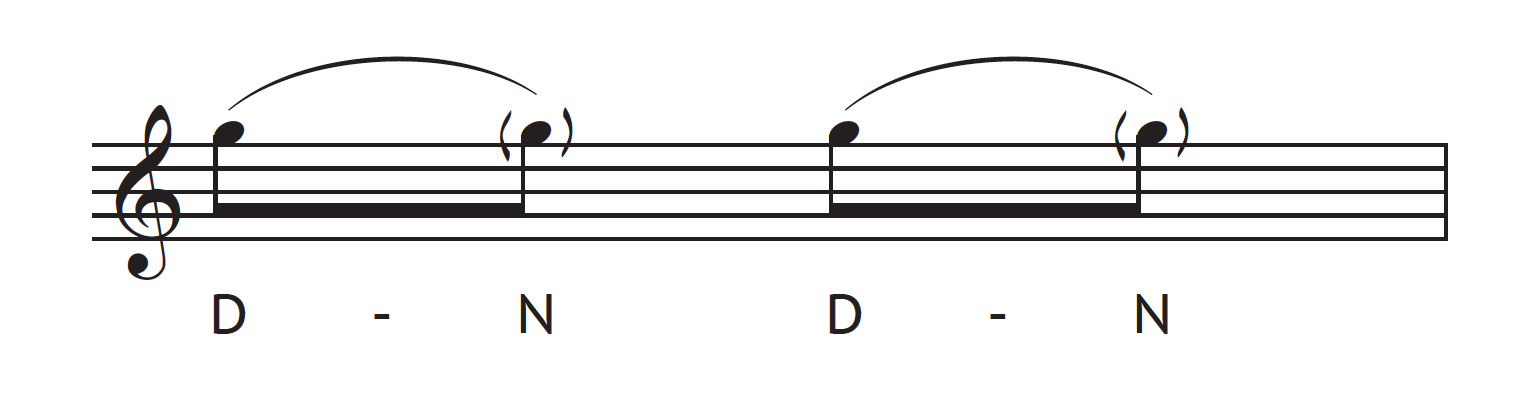

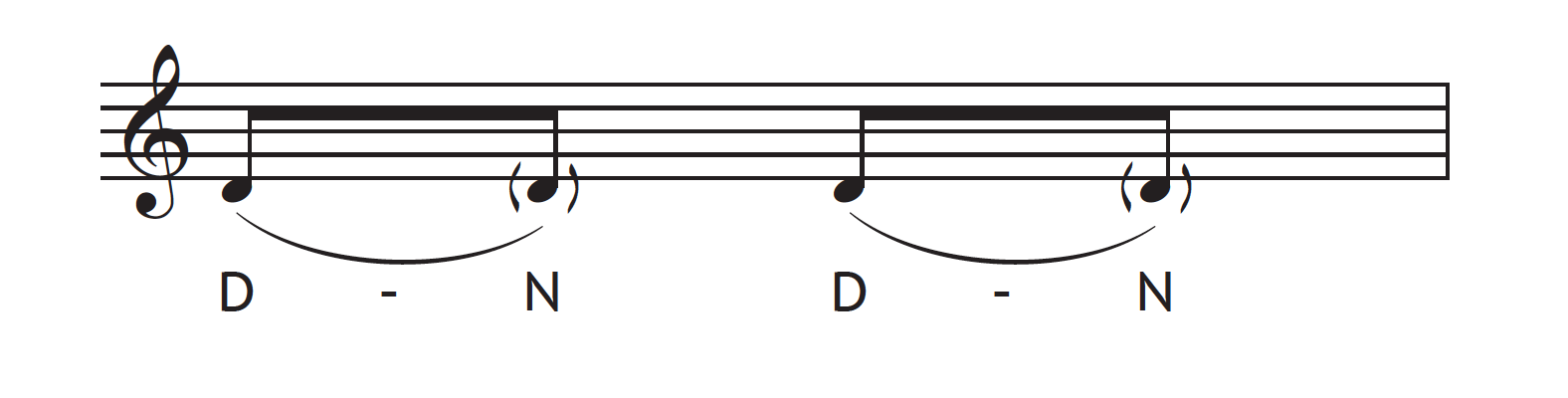

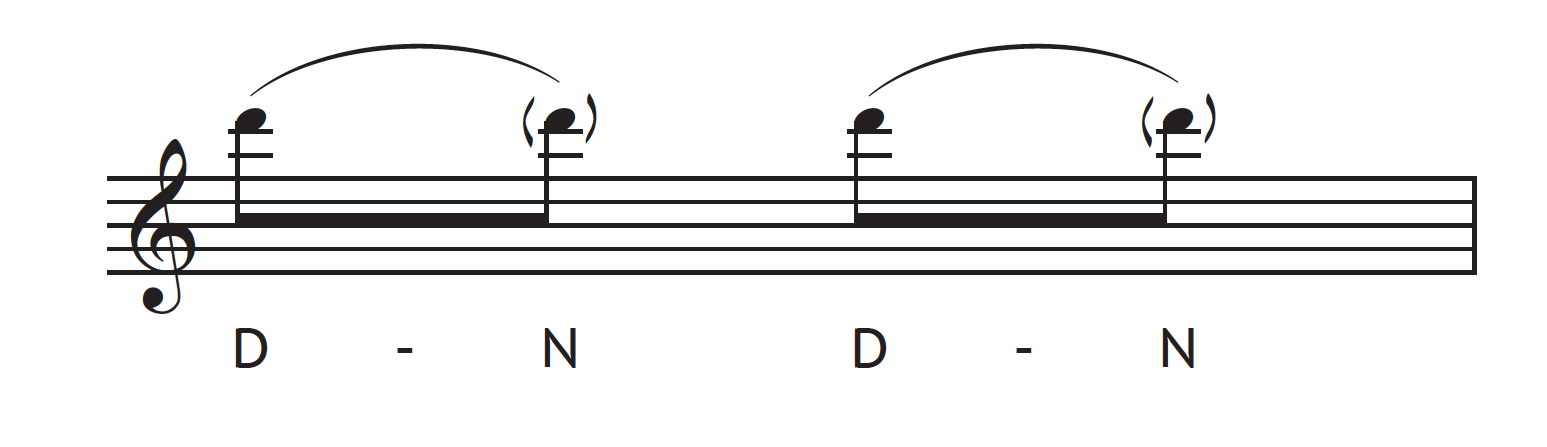

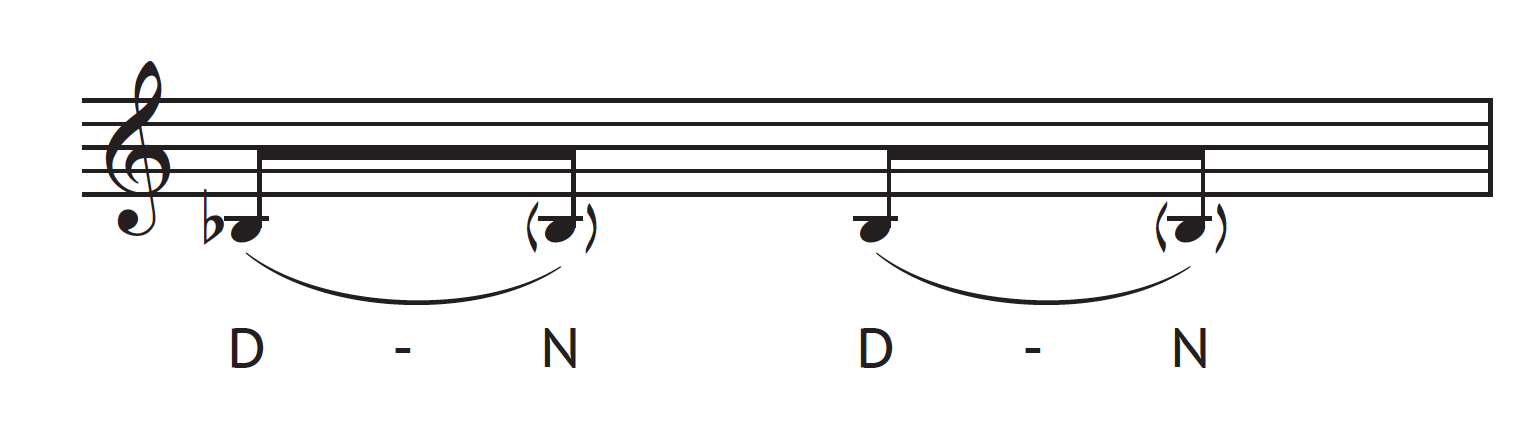

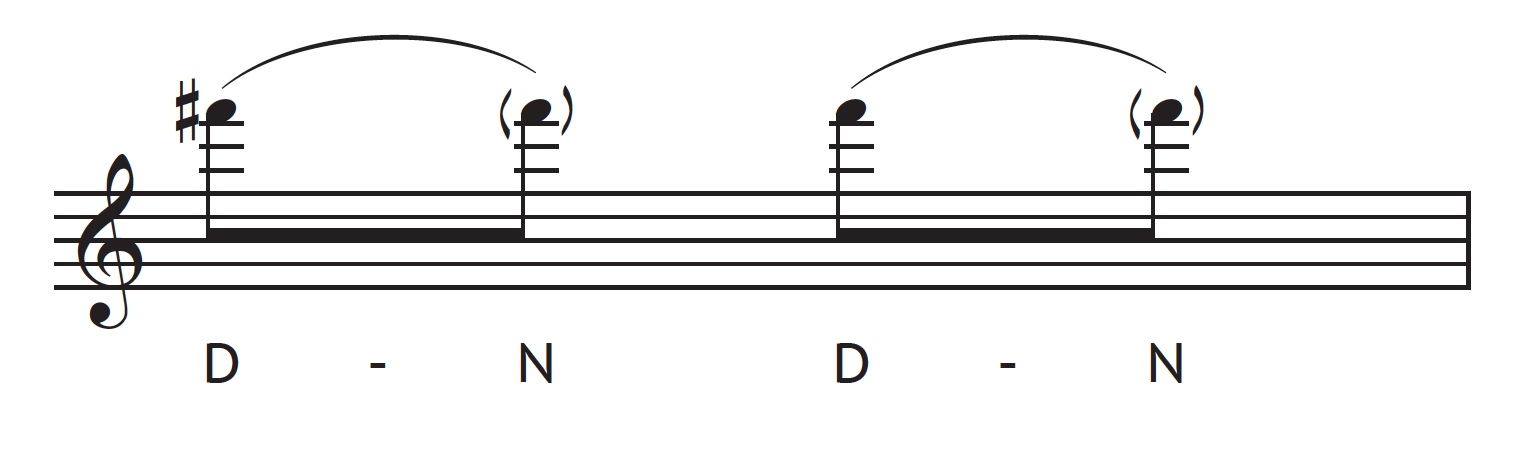

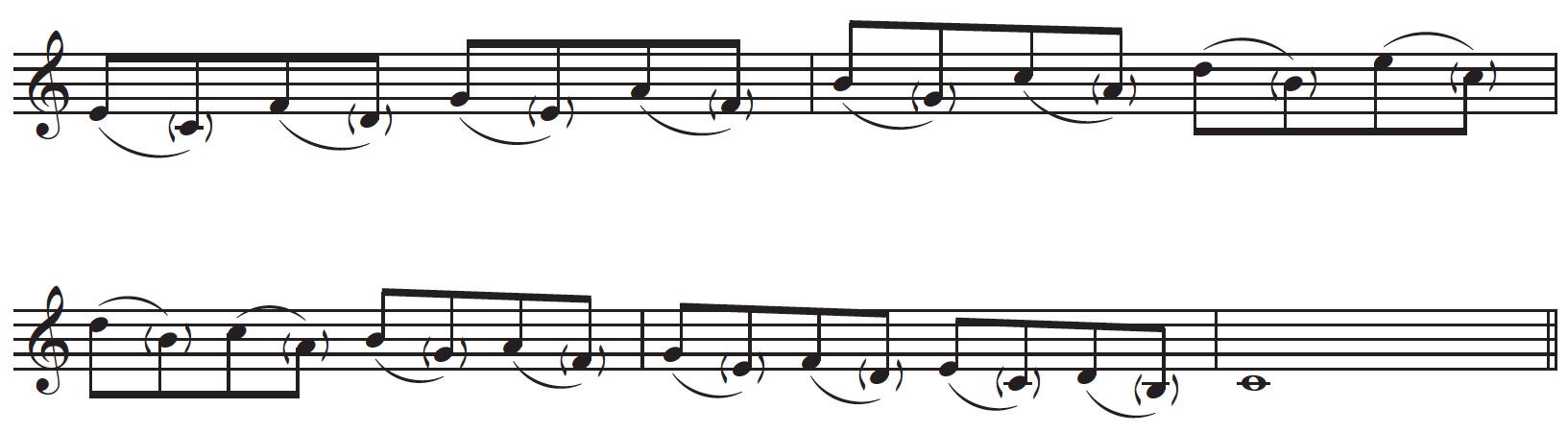

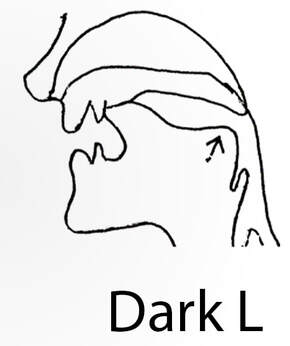

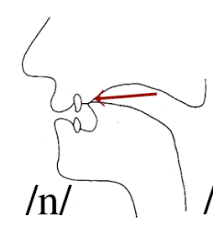

It's a big part of my mission to offer students and teachers simple and easy ways to master jazz style, especially when it comes to articulation. My concept involves basic saxophone phonetics, "Saxophonetics", that have greatly helped me and my students to improve technique.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed